ZINE MUNCH #6: Chomsky and the Kinkos Night Shift (at Interference Archive w/ Josh MacPhee)

On culture-making and social movements

Interference Archive is a non-profit, volunteer-run library and archive focused on “the relationship between cultural production and social movements.” On my way home from school in mid-May I plan a few days in New York City to interview people and visit physical spaces (more of these in the coming weeks!). I tell my friend Jasmine I’m planning to stop at Interference on Sunday afternoon and she asks if she can join.

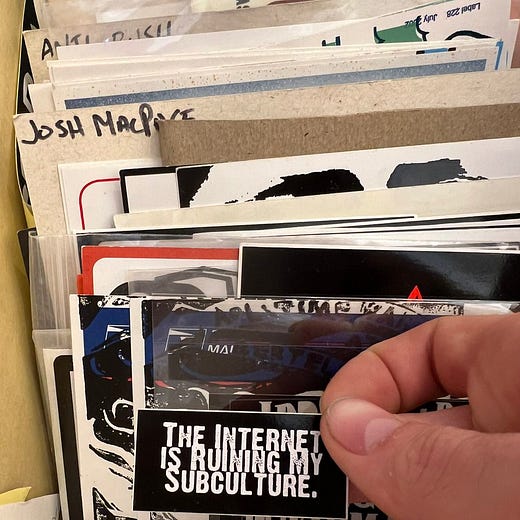

The archive is primarily focused on ephemera; it’s divided up into sets of boxes with labels like “stickers” and “media” along with sections for printed books and zines. It’s a blast to thumb through; I plan for a quick trip but we stay for almost two hours.

I learn about the archive on the recommendations of Heather Cole (Brown’s zine librarian) and Lindsay Caplan, my art history professor last semester who, it turns out, has been friends with one of the archive’s founders, Josh MacPhee, for several years. Josh is also a member of Justseeds, a cooperative of socially engaged artists and printmakers, and has published books like Paper Politics: Socially Engaged Printmaking Today and seven volumes of Signal: A Journal of International Political Graphics and Culture through PM Press. He’s made zines since he was in high school, including a zine Fenceclimber while studying as an undergrad at Oberlin. After far too quick stops Monday morning at ABC No Rio (currently ‘in exile’ at the Clemente Soto Velez Cultural center while their old space is rebuilt) and Bluestockings (I must go back!) I meet Josh outside the archive and we spend a few hours walking through Park Slope.

This interview has been edited for accuracy, clarity, and concision.

Lucas Gelfond: What drew you to zines or DIY culture in general?

Josh MacPhee: Punk. I had friends that are musicians, but I’m functionally tone-deaf, and I wanted to be just as much a part of the community as they were. Because punk encourages a broad egalitarianism, I could do that through publishing.

The first zine I made was called Blub. It was with a group of friends, it was a weird mix of bad poetry, doodles, and music reviews. I had a friend, Dennis, whose parents ran an instant print place. This was pre-copy shop, the sort of place where you’d get business cards made or letterhead. We would go and lock ourselves in [the print shop] on a weekend or when they were closed, and spend the entire day there. We would make copies of everything, print them out, and build these layout sheets on physical forms that were the size of the page, and then throw them on the copy machine, make copies. I was doing that from 15 years old to 18 or 19. We would sell Blub in the cafeteria at school. I was in high school when the US invaded Iraq in 1990/1991, and I started to get into political stuff. The experience of that led to doing Fenceclimber which was much more punk-identified and political. It had interviews with bands, but also much more directly political writing, music reviews, concert reviews, and book reviews.

LG: Even with access to a print shop like that, there has to be something that compels you to be in there, especially to take your Friday and Saturday—what motivated you to spend so much time printing stuff?

JM: This feels like it’s a cliche, but the world has changed so much in the last 30 years. When I was 17, one certainly could express oneself but there was no public outlet for it. There was no social media, there was no email, so the way that you thought about communication was one-to-one, a direct relationship. It wasn’t that you were a transmitter and there would be this open field of receivers, but publishing was a way to start to approach that broader spectrum communication.

Because there wasn’t this mesh of networked small-p publishing that was happening in the world, it was an exploratory process. It was like ‘for this set of ideas, as an artist and someone who’s sort of antagonistic to the status quo, who sees themselves as part of a counter culture—if these things matter, how do we communicate them to the world?’ Not only that, but how do we communicate internally as punks or political actors? That was a big part of zine culture.

LG: What do you think drives the connection between punk music and printed zines?

JM: ‘Zine’ comes from fanzine, and original fanzines were mostly not musical. There were some, for bands that had cult followings like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and the Grateful Dead, but there were a lot of zines that were about science fiction, or other genres like true crime that have become their own things online through fan fiction. That stuff started as part of zine culture, you’re not going to learn about what’s important to the people you see as your peers by reading Time Magazine.

All the media we had access to back then was so profoundly top-down, even more than mainstream media is now because there wasn’t the level of competition. Arguably, the media is more consolidated than it ever was, but at the same time, there’s an overwhelming number of outlets to get information from. None of that existed!

I lived in a town that didn’t have regular access to a college radios station, because I was too far away from Boston to effectively tune in—at that point in the 90s, most college radio stations functionally had micro transmitters, and they hadn't become large enough to reach outside of the direct area they were in. I remember fiddling with a dial for what seemed like forever to tune in to just the edges of the Framingham State station, which was the closest college to where I lived in Massachusetts. [They broadcasted an] interview with Chomsky when the first Gulf War was starting, explaining why we were invading Iraq. There was easy no access to that information, you had to fight with a 1980s radio to be able to get that.

It was all part of knowing, just knowing on a deep, profound level that there were people that thought like I did out in the world, but the only way to connect with them was to put yourself out there in some way. Making a zine was a way to do that.

LG: I’d assume you’ve met people through zinemaking, but do you think it was through distribution, or did people contact you?

JM: Yeah, totally. In 1994, two friends and I drove from Washington, D.C. to Oakland through the southern route, and we had friends that were in bands or did zines who we stayed with along the whole route. When we got to Houston, the people we were gonna stay with totally ghosted.

At that point, there were no cell phones, you would have made all these plans ahead of time by sending letters back and forth. You’d also use payphones; we built these things called “dialers” using little boxes you would get at RadioShack that you could reprogram to replicate the sound of dropping a quarter in the payphone. The payphone would recognize it as you putting a quarter in—punk was all really integrated with scamming culture because none of us had any money. You would basically travel and stop anywhere there was a payphone to call people, and the people we were staying with in Houston didn’t pick up.

We were like, ‘what are we going to do?’ So we roll into Kinkos at like 11:30 at night in the outskirts of Houston and just started copying zines. We just figured we’d stay there until someone came in who was a punk, and that’s exactly what happened. This crew of kids came in to make copies for a flier for a show and we went up and talked to them. They gave us a place to stay, brought us to the show, fed us—we had no idea who they were, it was just a tribal thing. You could do that, you knew that if you went into a Kinkos in any urban area and stayed there long enough, you would find someone who was coming in to copy a zine or make a punk flier and you would be able to connect with them.

LG: It sounds like a blast.

JM: Yeah, it was a different time, but I do think publishing was a big part of it. It’s hyperbolic to say that it was as or more important than the music, but zines, writing, and ideas mattered in that community. For instance, the riot grrl movement, the reason it got so huge was because Bikini Kill was a massively popular band—there were a whole collection of bands, but [the movement] started out as a zine, and the publishing wing was really important.

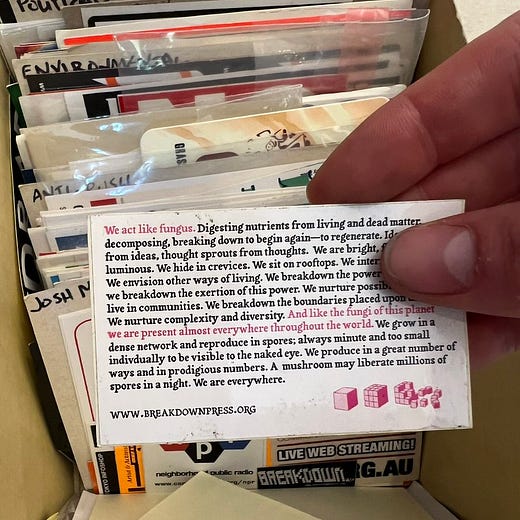

I was part of an infoshop in Washington D.C. called the Beehive, and one of the rooms was where Riot Grrl Press was. Young women across the country (and increasingly across the world) would send in what were called ‘flats,’ masters of zines that were stored in a central file cabinet. Anytime anyone wanted one of the zines, you’d just make a copy, it was a pre-internet open distribution model. People were experimenting with all this stuff; it was almost like print-on-demand, but it was physical, sitting in a file cabinet instead of on a server.

LG: What has changed about how you think through your own art and publishing practice?

JM: […] There’s so many contradictions in all of this, because on one hand, as we were talking about earlier, part of what got me here was this experience in high school of needing to find an outlet for self-expression, and for the past decade I’ve really been on something of a crusade against self-expression.

That’s part of why I like to figure out ways to play with or challenge authorship, because there’s a set of less visible realities that are a product of the valorizing of self-expression: for example, erasing the fact that all ideas are communal and all information is social. We never think of something on our own, it always comes out of discourse, and so the whole idea of individually authoring an idea, or the academic fetishization of authorship, I think is not only absurd but fundamentally violent as it erases the social, the things that connect us to each other.

The dominant discourse is a real head spinner, because on one hand it has valorized self-expression as the most cool, rebellious, radical thing you can do, and at the same time has precluded any other form of expression. If you take 30 seconds to think about it, it’s completely absurd. In some ways, individually it’s far more radical to just shut the fuck up. [And we certainly] live in a culture in which all forms of social expression are deeply policed and repressed.

LG: How do you think through effecting political change with publishing and media—is this a necessarily limited approach? What are some of the shortcomings of current approaches?

JM: My orientation to politics started out very activist, you agitate for the changes you want to see, raise awareness, protest—in the last decade I’ve become much more oriented toward community organizing models and assessing how power is wielded; there’s a huge difference between rhetorical politics and real politics. There’s a big difference between saying one’s an abolitionist or putting forth a position that there shouldn’t be prisons, and getting into the nitty gritty of doing the work to pass a law that literally gets people out of jail, which may on the surface look less abolitionist but, as a result, can actually decarcerate rather than make a good argument about decarceration.

We’ve seen that capitalism is very adept at skinning the surface off of almost anything and generating markets to sell it to. I think that identitarianism has profoundly influenced our society, but it hasn’t done an immense amount to shift actual power. Is it a good thing? In many ways, unquestionably. Should people be able to see representations of themselves or what they believe in the world? Absolutely. Is that different from actually having access to the capital and power necessary for your community to not be impoverished? Totally different things. I think that it’s ‘yes and’. We should influence the discourse, and we need to influence how power functions—we can’t accept rhetorical change in the place of structural change. These things are often pitted against each other, but we need both.

LG: Yeah, I worry some activism-oriented media can end up leaning fairly ‘folk-political.’

JM: Yeah, do you know Murray Bookchin? I’m probably butchering this at some level but he used to have this example involving an oak tree. If an oak tree drops an acorn, that may or may not grow into another oak tree, but it’s not going to grow into a car; we’re limited by the conditions that exist within it. There’s an embrace [in contemporary left politics] of magical thinking, which on one level is wonderful because it allows us to see outside the box to imagine new things, but that needs to be paired with a more dialectical way of understanding, something like ‘just because you want something to be doesn’t mean that it’s possible.’ Basically, the possible should not take the place of the imaginary, but the imaginary can’t take the place of the possible.

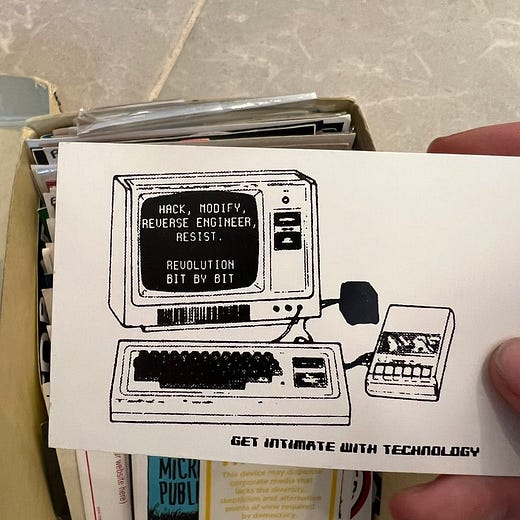

For me, building this archive of examples—Interference Archive—on one hand generates an imaginary, but on the other, is—ideally—an entire curriculum of what is possible or not possible. The dominant way people absorb information is from images, but we aren’t taught image literacy; we’re watching without necessarily having the skillset to interpret.

I see part of my role as teaching visual literacy to organizers so that they can understand how the language in their field is articulated and rearticulated all the time, and to [think through] ways to intervene into that. For example, when you can use images people already recognize or have relationships with, they’re more likely to connect to those images. In an art world context, the goal as a creator is coming up with something that’s novel, but it’s not the same for political organizing. While newness may be valorized in a movement context, there’s no inherent benefit; most often something that’s familiar is more effective at communicating your ideas.

I think a lot about contemporary meme culture when I teach people about image-making. Most of the value of a meme today is rooted in how esoteric it is. It becomes a marker of insider culture, because the more removed from its point of reference, and the more you need a lot more background to understand that, the cooler it seems to be. An insider culture, of course, is defined by the existence of an outsider culture, and to me this is a form of anti-politics. It’s a kind of nihilism, it accepts the idea that we couldn’t ever actually reach a critical mass of people who would be insider enough to ever change anything, so we just accept wallowing in the sort of humor and ‘coolness’ of how isolated we are. The political origins of meme culture are left iconography from the sixties, seventies, and eighties; all [of those contexts] acknowledged that more people recognizing an image makes it more valuable. Those movements trafficked in images that could be easily repurposed, reused, reinterpreted, and redeployed while maintaining a core goal of more justice for more people. We need more of that today.

You can follow Josh on Instagram, and also the Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative (which Josh founded) on Instagram and Twitter. You can also follow Interference Archive on Instagram and Twitter or visit (highly recommend!) their open hours in Brooklyn Fridays from 1-6pm, Saturdays from 12-5pm, and/or Sundays from 12-5pm. It’s really special to flip through some of this stuff physically, and to talk about the materials with others in their physical space—they’ve built a pretty remarkable community around it. What are your favorite physical artifacts or repositories of physical artifacts? (You can leave a comment or reply directly to this email!)

Until the next!

~lucas